Blue Light and Sleep: How Modern Screens Disrupt Your Body Clock

Key Takeaways:

- Counter-Intuitive Insight: Blue light is not inherently “bad”; it is biologically necessary during the day to signal alertness and mood regulation, only becoming detrimental after sunset.

- Specific Timeframe: Exposing your eyes to bright screens for just two hours before bed can suppress melatonin production by a significant percentage, delaying sleep onset.

- Biological Concept: Your eyes contain special non-visual cells (ipRGCs) dedicated solely to setting your body clock, distinct from the rods and cones used for vision.

- Realistic Expectation: Resetting a disrupted circadian rhythm due to chronic light exposure typically requires 3 to 7 days of consistent light hygiene to normalize.

In the modern digital era, we have effectively uncoupled our wakefulness from the sun. For millions of years, human biology relied on a simple, predictable signal to regulate energy and rest, the rising and setting of the sun. Today, however, we are bathed in artificial illumination long after dusk. While this has allowed for extended productivity and entertainment, it has introduced a complex biological conflict regarding blue light and sleep.

This conflict is not merely about staying up late to scroll through social media; it is a fundamental disruption of the neurochemical processes that govern recovery. When you stare into a screen at night, you are not just looking at pixels; you are sending a potent signal to your brain that it is still high noon. This miscommunication can lead to chronic sleep debt, reduced cognitive performance, and long-term metabolic issues.

Understanding the relationship between light spectrums and human biology is the first step toward reclaiming your rest. This guide will explore the precise mechanisms of how light influences the endocrine system, the physics of wavelengths, and evidence-based protocols to manage your environment. You will learn how to coexist with technology without sacrificing the deep, restorative sleep your body requires.

1. The Biological Mechanism of Blue Light and Sleep:

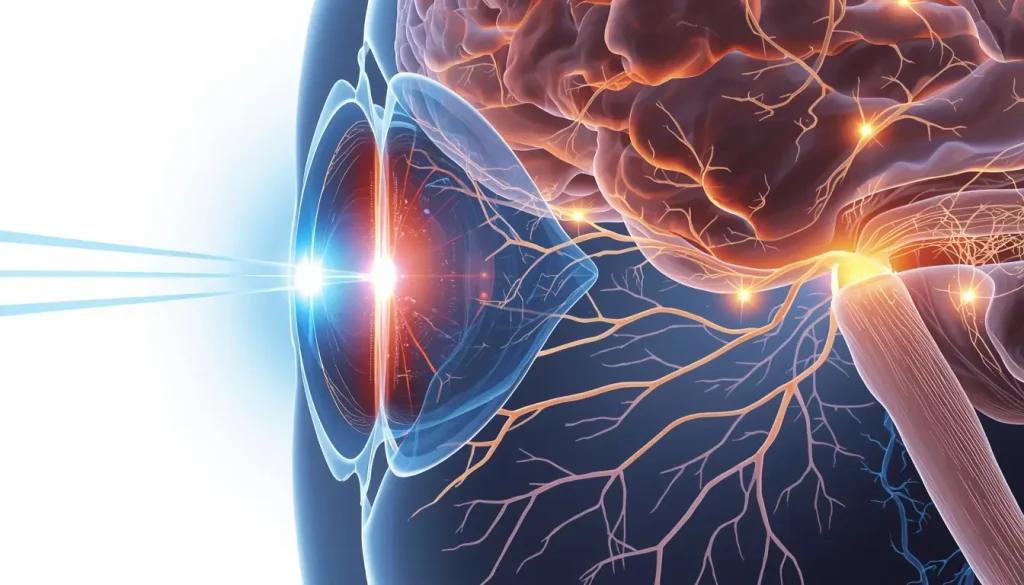

Blue light and sleep interact through a specific pathway where short-wavelength light (approx. 460–480 nm) stimulates specialized cells in the retina called ipRGCs. These cells send direct signals to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the brain to halt melatonin production, tricking the body into a state of daytime alertness.

The Role of Intrinsically Photosensitive Retinal Ganglion Cells (ipRGCs)

To truly understand how light affects us, we must look beyond standard vision. For decades, scientists believed that the eye only contained rods (for low light) and cones (for color). However, relatively recent discoveries identified a third type of photoreceptor: Intrinsically Photosensitive Retinal Ganglion Cells, or ipRGCs.

These cells are particularly sensitive to short-wavelength light specifically the blue portion of the visible spectrum. Unlike rods and cones, ipRGCs are not involved in forming images. Their primary function is non-image-forming phototransduction. When blue light enters the eye, these cells activate and transmit signals directly to the master clock in the brain. This system is so sensitive that even blind individuals with intact retinas can often maintain a synchronized circadian rhythm, proving that the pathway for light regulation is distinct from the pathway for sight.

This involves mimicking the natural transition of the sun within your living environment as part of a consistent evening routine.

The Suprachiasmatic Nucleus (SCN) Connection

The signals sent by the ipRGCs travel via the retinohypothalamic tract directly to the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus (SCN), located in the hypothalamus. The SCN is the body’s master pacemaker, coordinating the daily rhythms of almost every cell in the human body.

When the SCN receives the signal that “blue light is present,” it interprets this as “it is daytime.” In response, it coordinates a rise in body temperature, an increase in cortisol (the stress and alertness hormone), and improved cognitive reaction times. This mechanism is perfect for 10:00 AM but disastrous for 10:00 PM. The presence of blue light and sleep disruption is essentially a confusion of timing; the SCN is doing its job correctly based on the input it receives, but the input is artificially generated by our devices rather than the sun.

2. Melatonin Suppression and the Endocrine System:

Melatonin suppression occurs when evening blue light interferes with the brain’s hormonal signaling, preventing the endocrine system from initiating the biological transition from wakefulness to sleep. This disruption affects not only sleep timing, but also temperature regulation, cortisol balance, and overnight recovery processes.

Melatonin is often called the “sleep hormone,” but its role is far more sophisticated. It functions as a time-keeping signal that coordinates multiple endocrine systems at once, telling the body when to lower alertness, reduce core temperature, and shift into nighttime repair mode. When blue light enters the eyes after sunset, this signal is delayed or weakened, creating a mismatch between physical fatigue and hormonal readiness for sleep.

The Pineal Gland’s Function

The primary victim of evening light exposure is the pineal gland, a small, pea-shaped gland located deep in the center of the brain. Its main function in the context of sleep is the synthesis and secretion of melatonin, often referred to as the “hormone of darkness.”

Under natural conditions, as the sun sets and the spectrum of light shifts from the bright blue of day to the warm oranges and reds of dusk, the SCN signals the pineal gland to begin producing melatonin. This hormone does not “put you to sleep” like a sedative; rather, it signals to the body that it is time to sleep, initiating a cascade of physiological cooling and relaxation.

Quantifying the Impact of Suppression

Research indicates that the sensitivity of the melatonin system to light is profound. Studies from the Sleep Foundation and other major research bodies suggest that exposure to room light during the hours before bedtime can suppress melatonin onset by roughly 90 minutes.

This suppression creates a state of “circadian misalignment.” Your body might be physically exhausted, but your hormonal profile is that of someone in the middle of the afternoon. This discrepancy leads to increased sleep latency the time it takes to actually fall asleep once you are in bed. Furthermore, when melatonin is suppressed, it doesn’t just bounce back immediately when you close your eyes; the delay can push your entire sleep cycle forward, making it significantly harder to wake up the next morning.

3. The Physics of the Light Spectrum:

The visible light spectrum is measured in nanometers (nm), with blue light occupying the high-energy, short-wavelength band between 380 and 500 nm. The specific range of 460–480 nm is the most potent for circadian regulation, which unfortunately matches the peak emission of modern LEDs, smartphones, and tablet screens.

To effectively manage blue light and sleep, it helps to understand the physics of what you are seeing. Not all light is created equal, and the specific “color temperature” of a light source determines its biological impact.

Understanding Wavelengths and Nanometers

Light travels in waves, and the length of these waves determines the color we perceive. Blue light is characterized by short wavelengths and high energy. This is distinct from red or amber light, which has longer wavelengths and lower energy.

The specific band of blue light that has the most dramatic impact on circadian rhythms is often cited around 460 to 480 nm. This is the “sky blue” frequency that dominates the mid-day sun. Unfortunately, this is also the precise frequency heavily emitted by energy-efficient LED light bulbs and digital displays. These devices often have a “cool” color temperature (measured in Kelvin), frequently exceeding 5000K, which closely mimics the intensity and spectrum of daylight.

The Difference Between Day and Night Exposure

It is critical to distinguish that blue light is not a toxin. In fact, exposure to blue light during the morning and early afternoon is vital for health. It helps anchor the circadian rhythm, boosts mood, and improves reaction times.

The problem arises solely from timing. Evolutionarily, the only source of blue light was the sun. Therefore, the presence of blue light was a 100% reliable indicator of daytime. Firelight and candlelight, which humans used for thousands of years after dark, emit long-wavelength light (orange/red spectrum) and have very little impact on the melatonin system. Our modern environment has inverted this natural order, flooding our evenings with the specific wavelengths our biology interprets as a wake-up signal.

The Light Spectrum Guide Kelvin vs. Circadian Impact

| Light Source | Color Temperature (Kelvin) | Primary Wavelength | Biological Signal to SCN | Best Time to Use |

| Mid-Day Sun | 5500K – 6500K | High Blue (460–480nm) | Maximum Alertness (Stops Melatonin) | Morning & Noon |

| Smartphones / Laptops | 4000K – 6500K | High Blue (Peak Intensity) | False Daytime (Disrupts Rhythm) | Avoid 2 Hours Before Bed |

| Warm White Bulb | 2700K – 3000K | Balanced / Low Blue | Neutral (Minimal Stimulation) | Early Evening (Dinner) |

| Candle / Fire | 1500K – 1900K | High Red / Orange | Safe for Sleep (Melatonin Neutral) | 1 Hour Before Bed |

4. Impact on Sleep Architecture and Quality:

Beyond simply delaying sleep onset, blue light exposure alters sleep architecture by reducing the duration of Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep. This disruption can lead to a phenomenon known as social jetlag, where individuals wake up feeling unrefreshed and cognitively foggy despite spending enough hours in bed.

Many people focus on how long they sleep, but the quality and structure of that sleep are equally important. Blue light interferes with the internal sequencing of sleep stages, compromising the restorative value of your rest.

Reduction in REM and Deep Sleep

Sleep is composed of distinct cycles, including Rapid Eye Movement (REM) and Non-REM stages (including deep, slow-wave sleep). Chronic exposure to blue light before bed has been linked to a reduction in the amount of REM sleep a person achieves during the night.

REM sleep is crucial for cognitive processing, memory consolidation, and emotional regulation. When this phase is shortened, individuals may wake up feeling groggy or irritable. This reduction occurs because the delayed melatonin onset pushes back the timing of the entire sleep cycle, often cutting off the final, longest REM stages that typically occur in the early morning hours before waking.

The Cortisol Awakening Response

Healthy sleep architecture relies on a predictable curve of cortisol. Ideally, cortisol the stress and alertness hormone should be at its lowest point around midnight and rise sharply in the morning to help you wake up (the Cortisol Awakening Response).

However, if blue light exposure keeps cortisol levels elevated late into the evening, the natural trough is disrupted. This state of hyper-arousal can prevent the body from entering the deeper stages of restorative sleep efficiently. Over time, this chronic elevation of stress hormones due to artificial light exposure can contribute to broader health issues, including metabolic dysregulation and increased cardiovascular strain.

5. Digital Eye Strain vs. Circadian Disruption:

Digital Eye Strain and circadian disruption are two distinct issues caused by screens. Eye strain results from focusing fatigue and reduced blinking, while circadian disruption is a hormonal imbalance caused by specific light wavelengths. You can experience hormonal sleep disruption even if your eyes do not feel tired or strained.

It is common to confuse the physical sensation of tired eyes with the internal mechanism of wakefulness. Addressing blue light and sleep requires distinguishing between optical fatigue and endocrine suppression.

Distinguishing the Two Problems

Digital Eye Strain, also known as Computer Vision Syndrome, is caused by the physical act of looking at a screen. Factors include pixelated contrast, glare, and a significantly reduced blink rate, leading to dry eyes and headaches. This is a muscular and surface-level issue.

Circadian disruption, however, is invisible. It is the suppression of melatonin caused by the wavelength of light entering the eye. A person can stare at a screen and feel perfectly fine visually, yet their brain is chemically convinced it is afternoon. Addressing sleep requires specific attention to the light spectrum (color) and timing, whereas addressing eye strain often involves breaks and lubrication.

Why Brightness Matters

While wavelength is the primary factor for the circadian clock, intensity (brightness) acts as a multiplier. The photoreceptors in the eye integrate the total amount of photons hitting the retina over time.

This means that if you must use screens at night, lowering the brightness is a valid first line of defense. However, because the ipRGCs are exquisitely sensitive, dimming alone is often insufficient to fully mitigate the alertness signal if the light source is still rich in blue wavelengths. This is why changing the color profile of the screen (to warmer, amber tones) is generally more effective for sleep hygiene than simply lowering the brightness of a blue-tinted screen.

6. Behavioral Protocols for Light Regulation:

To reset your circadian rhythm, implement a ‘Sunset Protocol’ that mimics natural light transitions. This involves using warm 2700K lighting in the evening, engaging ‘Night Shift’ modes on devices two hours before bed, and utilizing blackout curtains to ensure total darkness during sleep for optimal melatonin preservation.

You cannot always control the world around you, but you can control the light environment within your home. Implementing structured protocols is the most effective way to protect your biology in a digital world.

The “Sunset” Protocol

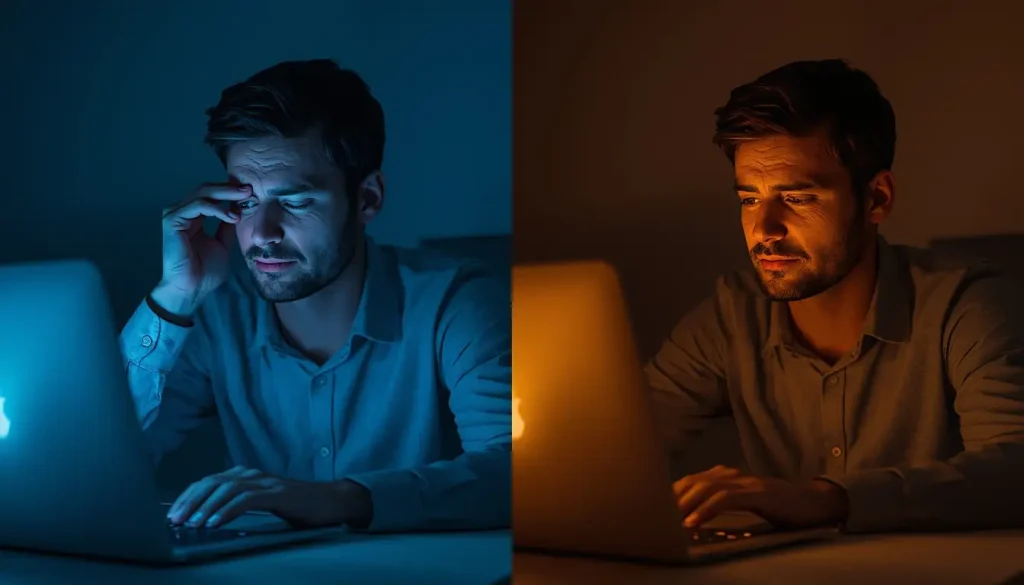

To harmonize blue light and sleep, you can mimic the natural transition of the sun within your living environment. This starts with a “Digital Sunset.” Two hours before your intended bedtime, significantly reduce screen usage. If total avoidance is impossible, engage mitigation strategies immediately.

Simultaneously, switch off overhead LED lights. Overhead lighting mimics the angle of the sun, which is highly stimulating to the SCN. Instead, rely on floor lamps or desk lamps positioned below eye level. Ensure these lamps use warm-colored bulbs (2700K or lower), which emit less blue light and more relaxing amber tones.

Leveraging Darkness

Complete darkness is the ideal sleep environment. Even small amounts of light pollution from streetlights filtering through curtains or standby lights on electronics can impact sleep quality and structure.

Using blackout curtains or a high-quality sleep mask can ensure that once you are asleep, you remain in a state of deep rest. For those who need to get up in the middle of the night, avoid turning on bright main lights. Using a nightlight with a red bulb allows you to see without triggering the ipRGCs, preserving your melatonin levels for when you return to bed.

Real-World Resilience:

The Shift Worker’s Adjustment Elena, a 34-year-old nurse, struggled for years with “flip-flopping” her schedule. Her nights in the hospital were bathed in bright fluorescent light, making it impossible to sleep when she returned home at 7:00 AM. She began wearing dark, wrap-around sunglasses during her commute home to block the morning sun. Inside her bedroom, she installed blackout shades and taped over the LEDs on her air purifier. By manually controlling the light entering her eyes, she was able to “trick” her body into believing 8:00 AM was midnight, allowing her to get 6 hours of restorative sleep instead of her usual fragmented 3 hours.

The Late-Night Designer Mark, a graphic designer, felt that his “creative hours” were late at night. However, he found himself exhausted and foggy every morning. He didn’t want to stop working at night, so he changed how he worked. He installed software that aggressively warmed his monitor’s colors after 9:00 PM. He also switched his office lighting from overhead panels to a single desk lamp with a vintage-style amber bulb. While he still worked until midnight, the reduction in blue light intensity helped him fall asleep within 15 minutes of finishing work, rather than lying awake for an hour with a racing mind.

Tools & Resources for Tracking Progress

In the pursuit of better sleep hygiene, several non-commercial, behavioral, and conceptual tools can be highly effective.

- The Kelvin Scale: Learn to read light bulb packaging. Look for “Warm White” or “Soft White” (2700K and below) for evening use, and reserve “Daylight” (5000K+) for workspaces during the day.

- Built-in OS Features: Most modern operating systems (iOS, Android, Windows, macOS) have built-in “Night Shift” or “Night Light” modes. Schedule these to turn on automatically at sunset. They warm the color temperature of your screen, reducing blue output.

- Red Light Therapy (Concept): Using pure red light bulbs in the bedroom lamps. Red light has the least impact on circadian rhythms and allows for reading or relaxing without hormonal disruption.

- The 20-20-20 Rule: Primarily for eye strain, but helps with mindfulness: Every 20 minutes, look at something 20 feet away for 20 seconds. This breaks the hypnotic lock of the screen.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ):

Q: Does “Night Mode” on my phone fully protect my sleep?

A: While Night Mode reduces the amount of blue light emitted, it does not eliminate it entirely. It also does not change the cognitive stimulation of the content you are consuming. It is a helpful tool, but not a perfect solution.

Q: Do blue light blocking glasses actually work?

A: Research is mixed, but the consensus is that glasses with amber or orange lenses are more effective than clear lenses with a blue-light coating. Amber lenses physically block a larger portion of the blue spectrum, which is necessary for preventing melatonin suppression.

Q: How does blue light affect children compared to adults?

A: Children’s eyes are actually more transparent than adults’, meaning they transmit more light to the retina. This makes them potentially more susceptible to melatonin suppression from evening screen use. Strict light hygiene is often even more critical for developing brains.

Q: Is all blue light bad for you?

A: No. Blue light is essential during the day. It boosts alertness, helps memory, and elevates mood. Lack of blue light exposure during the day (such as working in a dim office) can actually weaken your circadian rhythm, making it harder to sleep at night.

Q: Can I reverse the effects of blue light exposure?

A: Yes. The circadian system is plastic and adaptable. By consistently adhering to a light/dark cycle getting bright light in the morning and avoiding it at night you can reset your body clock within a few days to a week.

Final Verdict:

The relationship between blue light and sleep is a cornerstone of modern health. It is not about demonizing technology, but rather understanding the biological cues that our bodies have relied upon for millennia. The light entering your eyes acts as a powerful drug, capable of stimulating alertness or permitting rest.

By treating light as a biological input rather than just utility, you can gain control over your energy levels and recovery. The science is clear, protecting your eyes from short-wavelength light in the evening is one of the most effective, natural ways to safeguard your endocrine health and ensure deep, restorative sleep.

Try applying just one light-management change tonight and observe how your sleep responds over the next few days.